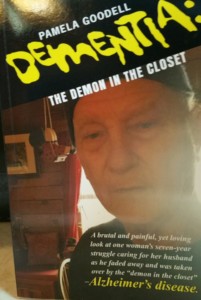

Dementia: The Demon in the Closet is a compelling book of a caregiver’s first-hand experience with the trials of her husband’s dementia, offering valuable credibility.

Written from a uniquely honest perspective, including medical and neuropsychological reports and references, nothing about dementia is “sugar-coated” in this personal account. Though brutal and painful, it is also loving and offers hints and advice on ways to deal with Alzheimer’s behaviors. It is meant to corroborate and validate the feelings of other caregivers, family and friends and to educate professionals, doctors, nurses and anyone else interested in this demonic disease. pam11

The book sells for $24.95 and can be purchased from:

- The author at: goodellpr@yahoo.com (please put “book” in the subject line)

- www.amazon.com (insert complete title)

- www.toadbooks.com (Toadstool Bookshops, NH)

I do not have a site of my own, but I do have an author’s page on Amazon (Pamela Goodell)

Statement of Purpose

My purpose in writing Dementia: The Demon in the Closet was to help others, especially caregivers, but also family, friends, and professionals to comprehend more fully what Alzheimer’s can entail in daily life. It is written from my actual personal experiences with my husband’s dementia. I am hoping that caregivers will not feel as alone after reading it; that they and others will be able to relate to the many ups and downs and find solace in the fact that I understand their situation. Perhaps they will be a little more prepared emotionally for what may come, what is happening, or what occurred in their caregiving journey.

Pamela Goodell

Here is a review of the book from the “The Keene Sentinel” in Keene, NH.

Descent into the abyss

Richmond author reflects on the disease that ravaged her husband

By STEVE SHERMAN

Contributing Writer

“Dementia: The Demon in the Closet” By Pamela Goodell

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 301 pages, $24.95

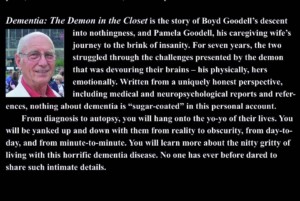

If love is seeing in someone what others do not, Pamela Goodell of Richmond has acted upon the vale of tears for the last seven years with her husband.Boyd Ellis Goodell died of dementia on April 20, 2015. He was 76 years old, a Naval radioman, Community Kitchen of Keene volunteer, youth baseball coach, truck driver, builder of the Pamela and Boyd log home — and Pam’s best friend.

He was the fourth child born in his family, and healthy most of his whole life. He opened his house to many foster children through the years, and loved nature. He was 69 years old when symptoms began, 71 when he was diagnosed with dementia. Boyd’s illness began with confusion. It progressed through moodiness, depression, excessive sleep, sleep disturbances, paranoia, visual hallucinations, disorientation, flatness of affect, loss of emotion, forgetfulness, impulse actions, anger, obsessiveness, difficulties with language, conversations and understanding, talking and mumbling constantly, lack of recognition of people, objects and food, threatening and violence.

There was a gradual loss of caution, but periods of clarity remained.

“In spite of the demon of dementia,” Pamela writes, “I would not trade having known Boyd for anything in the world. The first 23 years of our life together were the best and happiest of my life. I could feel his love in everything he did. He truly cared for me.”

Pamela Goodell’s courageous, bare heart book, “Dementia: The Demon in the Closet,” needs the loving counterweight from readers that she herself must have gathered to write about the anguish of living with dementia.

“In January 2008,” she writes, “Boyd was scooping snow off the deck when he ripped a tendon in his rotator cuff. Two days later he fell on some ice, landed on the same shoulder, and finished the job of tearing it to shreds.”

Boyd was instructed to anticipate being immobile for at least three months.

Her own gathering storm, she writes, started that day and rarely left during the next seven years.

Boyd had been under general anesthesia for more than two hours while the surgeon repaired the massively ripped shoulder. Medications included 15 drugs ranging from epinephrine to morphine. “Five are narcotic opioids,” she said. “Many are riskier when given to the elderly, frequently considered to be those 65 or older. Boyd was 69.”

Boyd’s professional therapy sessions lasted six months and then continued at home for the rest of a year.

“Now, however,” she writes, “I realize something important. Boyd’s brain never cleared up completely from 2008 forward.”

Nevertheless, Boyd still could not resist the call of the woods and waters. She pointed out a clipping from The Keene Sentinel about Boyd when he gave a reporter a walking tour headlined: “Walking with Boyd Goodell to Seven-Level Falls Keeps You Alert to the Sights and Sounds of the Woods. They Were the Nurturing Territories of Goodell’s Youth and Still Are Today.”

The fluctuations of Boyd’s smoldering ups and downs settled down in the middle of 2009. Pamela writes: “He resumed his typical chores of maintenance around the house. He cut wood and installed new parts for the wood stove. He caulked, changed the water filters, and installed a dimmer switch.”

Throughout 2008, 2009, and 2010, “I had begun to notice little things in Boyd’s behavior. I tried to ignore them. I tried to think my imagination was working overtime.”

Boyd then began repeating questions. Pamela asked him if he remembered that she had just given him the same answer. He began having trouble expressing and understanding ideas. He was confused a lot. He began forgetting things. He could not draw a clock with all the numbers and hands correctly placed, when asked to set them to a certain time.

The two of them collected ideas to reduce some cognitive decline, including weight loss, low-fat diet, regular exercise, a daily walk and word searches. They emphasized a highly consistent routine, such as meals at scheduled times, and walking and sleeping at the same time each day.

“When Boyd couldn’t start measuring a board on a home repair project,” she wrote: “Here was a man who had built our whole house out of logs and now he couldn’t even measure boards or figure out how to assemble them. This was the moment I realized we were dealing with a terrible disease, and that life would never be the same.”

She inevitably thought back to April of 2008. “My belief is that the anesthesia from his rotator cuff surgery caused, or triggered, or propelled a reaction in his brain which led to his dementia. Most doctors and those in the medical field ignored me when I stated my theory. Finally, however, one of Boyd’s primary care physicians did admit to me that ‘they’ were beginning to suggest that everyone over 65 years of age should avoid general anesthesia if it were not absolutely necessary. Anesthesia is given to make the brain forget pain and all other conscious memory. In some patients it appears that anesthesia and other medications that affect the brain can cause permanent memory loss problems.”

There is no cure for dementia, Pamela writes, and it is most often progressive. Dementia affects a person’s memory and ability to think and reason. As it progresses, dementia can also cause confusion, trouble with communicating, difficulties with words and numbers, poor balance and behavioral changes. The onslaught of dementia, an umbrella term, can lead to depression, anxiety, moodiness, paranoia and delusions.

Driving increased his stress. Pamela relates a typical scene with Boyd in her mother’s driveway in 2012, four years after demon dementia first appeared: “No, Boyd, I will NOT get out of the driver’s seat! I am your wife who loves you and wants to keep you safe.”

“Bull!”

“This argument goes on for a good fifteen minutes, but I do not give in. Boyd has been driving aggressively, has missed some yield signs, has gotten lost once, and has started hollering at other drivers as he cuts them off.”

Pamela has taken over all the out-of-town driving. “In fact,” she writes, “I do all the driving when we are together. I am too stressed at his driving to ride with him anymore, though I used to have complete confidence when he drove. When I’m not with him, he continues to only drive locally.”

Boyd’s periods of clarity and periods of confusion jumped back and forth from minute to minute, all day, every day. He remembered how to start and drive the lawn mower but could no longer steer around the rocks. Twice that summer they had to have the mower blades straightened.

“My optimism about the new Wellbutrin medication was short-lived,” she writes. “It certainly was not helping to keep Boyd calm in any way. On a trip to his favorite places in Maine, he was impatient and short-tempered. I told the neurologist the medication wasn’t helping and, if anything, was making Boyd worse. Instead of stopping the medication, the doctor doubled the dosage. Did he even listen to me?”

She called the doctor the next day to have Boyd taken off Wellbutrin and to cancel any further appointments with that doctor.

Pamela carried business-size cards to offer strangers explanations about his behavior:

“Dementia is an illness that sometimes results in awkward moments. Thank you for understanding.”

Steve Sherman reviews books related to New England by subject or author on alternating Sundays. Please submit newly published books and a news release to The Keene Sentinel, 60 West St., Keene N.H. 03431 or query stvsherman@aol.com.